Sometime in the last year, I began a faith deconstruction, and I realise that this is a terrible way to start this post as I don’t even know where to begin describing what that means. What have I deconstructed? Why? What prompted it? What does my faith consist of now that I’ve deconstructed? Have I started reconstructing or am I mostly just sitting around looking lost and wondering what I even believe any more?

I stumbled across this post from Unfundamentalist Christians today and it kind of put into words what I’ve been struggling to explain:

“I’ve asked about every troubling question you can imagine, and yet my faith remains intact. It’s a lot less comfortable than before, and in some ways barely recognizable, but it’s also deeper, richer, and more authentic. It’s constantly changing too, which can be exhausting, but also kind of exhilarating.”

I still believe that God exists so I guess my faith is (mostly) intact, but I’m definitely right in the middle of the constantly changing, exhausting part of reconstructing my beliefs, with the exhilarating moments few and far between. Occasionally I find something that really speaks to me in the midst of this weird deconstruction, and it’s incredibly freeing to realise that other people believe the same things as me–not just in the sense of “God exists”, but “God exists and we should dismantle the patriarchy”. Just knowing that I’m not alone and that other people have come to the same conclusions makes me feel a whole lot saner and a bit less heretical.

One of the conclusions that I’ve come to in the midst of my deconstruction, is that I’m an Anarchist. I mean, I already call myself a Feminist and confuse the heck out of a lot of conservative Christians, so why not add Anarchist into the mix as well to make things even more controversial? I’m not entirely sure when I started labelling my beliefs this way. I have a wonderful, amazing friend–whom I’ve only known for two years but it feels like she’s been there forever–who frequently writes posts on Facebook about her anarchist beliefs, and at some point during the two years we’ve known each other, my internal responses shifted from “This is intriguing but also kind of crazy” to “All of this makes complete sense and I entirely agree with it”. Not going to lie, my utter anger at the post-Brexit, post-Trump world kind of ignited my desire to align myself with anarchism, but it was a gradual process and entirely accidental. I didn’t go looking for anarchism–it found me, or I fell into it, or some other cliche.

So, what even is anarchism, and how has it somewhat saved my faith in God and humanity, and well, just everything? As much as I suck at describing my faith, I also kind of suck at describing anarchism. It’s super tempting to describe what anarchism is against rather than what it advocates for–which, admittedly, kind of happens with Christianity a lot as well. I was initially going to quote from Mark Van Steenwyk’s That Holy Anarchist (which is amazing because it helpfully brings together many of my beliefs in one accessible place and if you’re even remotely intrigued by Christo-Anarchism you should read it because it’s available for free here) but I discovered that Jesus Radicals (to which Van Steenwyk contributes) has a more coherent explanation:

“Anarchism is the name given to the principle under which a group of people may organize without rule. It is being against one group or person having “power over” others. For us, anarchism begins with naming and resisting those things that oppress, rejecting social hierarchies that place one group of people over another. Anarchism rejects the logic that places some over other on the basis of race, ethnic or cultural background, legal status, social status, class, gender, sexual orientation, age, ability, or any other rationale used for one group to exercise domination over another. It means challenging capitalism with its social inequalities based upon private property and wage labor and instead envisioning a society that emphasizes cooperation, mutual aid, holding land in common, and workers sharing ownership of the means of production. It means committing ourselves to undoing the legacies of oppression that have been passed down to us as we seek to build communities of hospitality and inclusion.”

In That Holy Anarchist, Van Steenwyk writes that:

“Anarchists are rarely simply against the State—they have (or should) become namers of all forms of oppression, seeking to understand the way oppressions reinforce each other in enslaving creation and seeing, in contrast, a way of liberation and life for all of creation.”

To those who call themselves Christians, this idea of liberation shouldn’t sound particularly radical, because supposedly our faith is about bringing about the liberation of all creation too. That’s not to say that anarchists have just hijacked Christianity and taken Jesus out of it and attempted to rebrand it as their own thing. Anarchism may be considered revolutionary, but it’s not a new movement in any way. Anthropologist David Graeber writes that:

“The basic principles of anarchism—self-organization, voluntary association, mutual aid—referred to forms of human behavior they assumed to have been around about as long as humanity. The same goes for the rejection of the State and of all forms of structural violence, inequality, or domination…even the assumption that all these forms are somehow related and reinforce each other. None of it was presented as some startling new doctrine. And in fact it was not: one can find records of people making similar arguments throughout history, despite the fact there is every reason to believe that in most times and places, such opinions were the ones least likely to be written down. We are talking less about a body of theory, then, than about an attitude, or perhaps one might even say a faith: the rejection of certain types of social relations, the confidence that certain others would be much better ones on which to build a livable society, the belief that such a society could actually exist.”

If Anarchism has basically been around forever, so has Christo-Anarchism. Van Steenwyk devotes an entire chapter in That Holy Anarchist to Christian movements whose actions have overlapped with anarchism, from the early church right up to the current day. This isn’t some ridiculous new idea that I’ve dreamed up to try to rebuild a faith in the midst of my Trump-prompted deconstruction, some amusing but unrealistic concept dredged out of sleep deprivation and near-delirium from too many mornings spent watching Team Umizoomi with my toddler. Christo-Anarchism (or whatever you want to call it, because apparently no one can decide on an official title) is an actual thing, a thing that people other than me practice. People have been doing it since Christianity existed (you could even be totally radical and argue that it is Christianity), and it just, well, makes a lot of sense.

Christianity that is infused with capitalism, imperialism and patriarchy, that both props up and relies on oppressive political powers while somehow simultaneously discouraging its followers from being “too political” (how does that even make sense?), that doesn’t actually succeed in helping our neighbours beyond telling them the Good News of Jesus, that creates a community that consists of occasional casseroles and platitudes and promises of prayers and not much else—is not what Jesus advocated for. I’m not sure how we ever convinced ourselves that it was.

I’ve believed in God for too long to simply abandon the possibility that he exists, but I need to be part of a faith that allows me to criticise and challenge (and possibly even dismantle) structures of power, that allows me to admit that the rampant imperialism in the Old Testament and Christian history in general is actually pretty uncomfortable. A faith that confesses that it created and contributed to many of the problems in the world, and that’s ready to fix them. A faith that isn’t just for the gainfully employed hetero-normative middle class. A faith that looks around the world and shouts “THIS ISN’T WORKING.” A faith that sees our capitalist, patriarchal, oppressive society and believes that this is not what Jesus’ kingdom is supposed to look like.

Back in November, I seriously struggled to see Jesus anywhere. I couldn’t see him in the colleagues who had voted for Trump and stood behind their decision. I couldn’t see him in the friends who tried to tell me that it wasn’t really that bad, that we just had to wait and see how things panned out. I couldn’t see him in the prayers and the platitudes and out-of-context Bible verses that were spouted in an attempt to convince me that everything would be okay if I just had faith and kept believing. I really struggled to see him anywhere at all, to be honest. But there’s this small anarchist community in my city–where I have one friend who I met through a freaking breastfeeding group, of all places–who actually seemed to be angry about all the same things as me. They didn’t stop being angry after a couple of days or weeks. They attended protests and held discussion groups where they talked about topics like mutual aid and solidarity, which felt like the kind of things my Bible study group should be discussing, to be honest. They seemed to care, to want to change things, to not want to put up with the way things are. It sounds utterly ridiculous, but the one place I saw Jesus was in the anarchists, and the more I read about their beliefs, the more I felt like I’d found my home.

I’ve been hesitantly owning the Anarchist label for the last six months, and reading That Holy Anarchist confirmed a lot of the ideas that I’ve been mulling over. I don’t feel quite so crazy for believing that Christianity and Anarchism can line up, that this fusion of beliefs does make sense in some way;

“Since Jesus is (as Christians believe) the truest revelation of God, then he defines for us what the reign of God looks like. The social, economic, political, and religious subversions of such an un-reign are almost endless—peace-making instead of war mongering, liberation not exploitation, sacrifice rather than subjugation, mercy not vengeance, care for the vulnerable instead of privileges for the powerful, generosity instead of greed, embrace rather than exclusion. Jesus is calling for a loving anarchy. An unkingdom. Of which he is the unking.”

Our faith has never been about gaining power, and I don’t believe we’re only called to challenge the world in a spiritual sense. If we’re called to love our neighbour, then we’re also called to advocate for them, to bring them out of oppression–and perhaps it’s entirely necessary to bring about freedom from earthly oppression before we broach the subject of spiritual liberation. Maybe dismantling systems of oppression is a form of evangelism. Sometimes loving our neighbour might require us to be uncomfortable, to take a stance that is neither polite nor neutral, to stand beside those who don’t share our faith but do share our desire to completely do away with all forms of oppression forever. As Van Steenwyk writes;

“In the early days—the first century of the Jesus movement—the church was invisible to most people in the Roman empire. However, they had a growing reputation as an alternative and seemingly antisocial community that lived in the nooks and crannies of Empire.

Christians were thought to be extreme, subversive, stubborn, and defiant. The Roman writer Tacitus called them “haters of humanity.” They rejected the central facets of Roman religious and political life. In his view they actively undermined society with their indifference to civic affairs. Some critics even blamed Christians for the fall of Rome.”

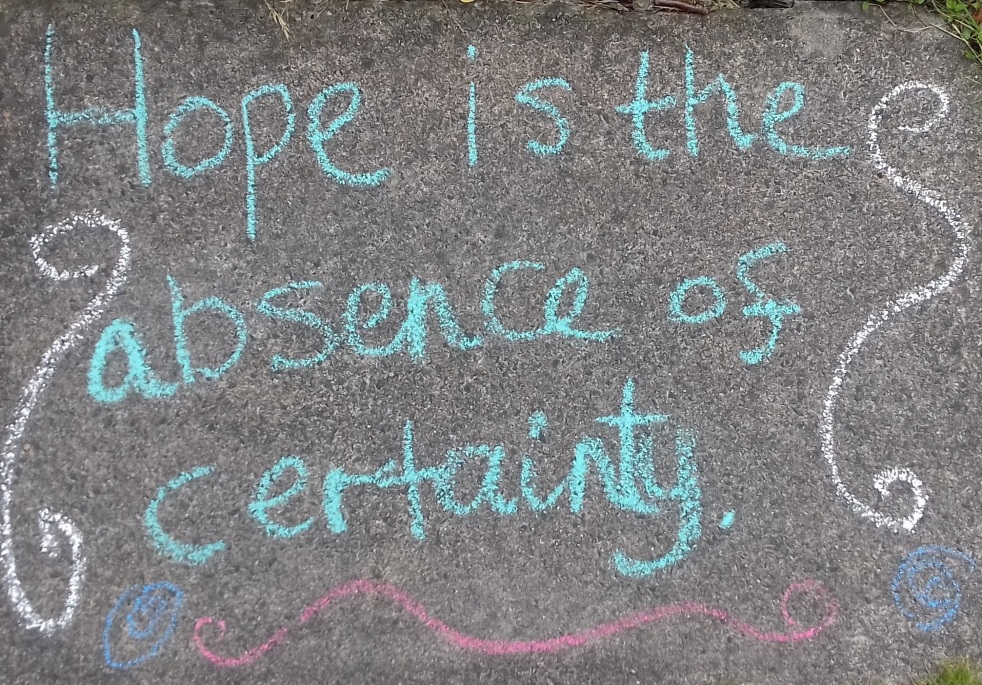

I can’t do comfortable, privileged, neutral Christianity any more. I want the subversive kind that seeks to undermine societal norms and systems of oppression, but I’ve seriously struggled to find this radical, disruptive form of Christianity in the church. Reading That Holy Anarchist and discovering that Christo-Anarchism is an actual thing has made me feel a bit less alone. Realising that there are other people who are just as frustrated and disillusioned as me has given me hope that I’m not alone in my anger and desire to change things.

I still don’t really know what I’m doing, and I feel like I should add a disclaimer stating that I’m not an expert on either Christianity or Anarchism, but this is where I’ve ended up. I’m not sure if Anarchists want me or if Christians will finally deem me too heretical to use their label any longer, but here I am. 2017 is turning out to be a pretty insane year, and Christo-Anarchism is one of the few things that makes sense.